POLYVAGAL THEORY

Polyvagal Theory describes the primary role of the ANS (Autonomic Nervous System) in shaping thoughts, feelings, behaviours, and beliefs (Porges, 2007). The fundamental premise of Polyvagal Theory is that human beings need to not only feel safe, but to feel safe in connection with others for survival. At the same time, human biology is fiercely devoted to preventing harm. Often, this sets up a conflict between the drive to survive and the need to connect. The body’s rapid-response survival system is orchestrated by the ANS.

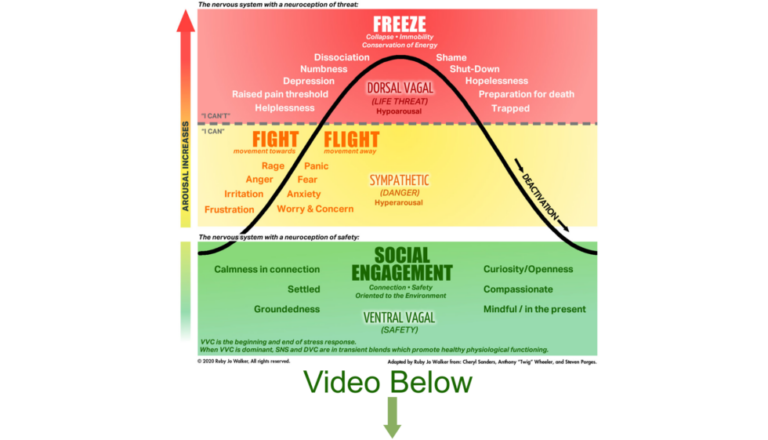

To briefly review, the autonomic nervous system operates two branches: the sympathetic and the parasympathetic. The sympathetic branch mobilizes a defence against danger through the fight-or-flight response while the parasympathetic branch has typically been viewed as a system that helps to lower defenses and regain a state of calm. Polyvagal Theory offers an updated understanding of the ANS showing that the parasympathetic branch in fact has two divisions of its own, one with the potential to create social engagement and connection, and the other that activates collapse and disconnection. These three pathways operate in a predictable hierarchy of response: ventral vagal – connection, sympathetic – fight and flight, dorsal vagal – disconnection. There is a default preference to be in ventral vagal safety and connection. When events in daily life bring too great a challenge for the capacity of the autonomic nervous system, the autonomic state shifts downward into sympathetic fight and flight and, if that does not resolve the challenge, the final move to the bottom of the hierarchy into dorsal vagal collapse and disconnection takes place.

While the sympathetic nervous system is made up of spinal nerves in the thoracic and lumbar region, the parasympathetic nervous system is a cranial nerve system with the vagus nerve (Cranial Nerve X) as the primary component. Starting at the base of the skull and winding to the abdomen, the vagus connects to the pharynx, larynx, heart, lungs, digestive system and other organs. Normally referred to in the singular, the vagus is actually a complex circuit of nerves divided into two pathways – ventral and dorsal – each responsible for a distinct neurophysiological state. The ventral vagal pathway supports a sense of regulation and readiness for social engagement while the dorsal vagal pathway enacts a move out of connection into collapse. The ventral vagus also moves upward from the brainstem connecting with four other cranial nerves (CN V, VII, IX, XI) to form the Social Engagement System. Sometimes called the safety circuit, the Social Engagement System uses eye gaze, facial expression, tone of voice, head movements, and social gesture to create safe connections with others (Porges, 2004).

Through autonomic processes, this internal surveillance system works in the background reading subtle signals of safety or threat. This moment-to-moment search for cues for safety and danger operates beneath awareness without involving the thinking parts of the brain, in what Stephen Porges describes as neuroception (Porges, 2004). Through the ongoing neuroception process the ANS scans for cues of safety and danger, initiating actions in service of safety and survival. While we do not always recognize the cues of safety and danger, we feel the physiological response. And, because humans are meaning-making beings, what begins as the autonomic experience of neuroception travels to the brain and becomes the story that directs daily life.

From a dorsal vagal or sympathetic state, danger rules and the story is one of survival. It is only from a ventral vagal state of safety and connection that the story can be one of hope and possibility.